As most readers will know, I have both a personal and professional interest in Type 1 Diabetes. Alongside living with it, I’m also a medical student, so I have the privilege of seeing a lot of stuff on both sides of the discussion. None of this is medical advice – if you are worried about your feet, go see your GP.

Diabetic foot disease is something that lots of people are either terrified of, or completely ignorant of – and neither of these things are good.

Diabetic foot disease is an important and serious complication of diabetes, but it is not inevitable, and a bit of care and attention for your feet can largely avoid some of the worst forms of it.

I promise there’s no gross photos in this post.

Well, what’s the problem?

Diabetic foot disease is serious business.

According to the National Inpatient Diabetes Audit 2015, People with type 1 diabetes are more than twice as likely to be admitted to hospital as a direct result of their diabetes than people with type 2 diabetes.

One in five of these will be admitted due to their foot disease.

There are 135 amputations performed a week on patients with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes.

Lots of people live a normal life after an amputation, but the objective should be not to need to learn to walk again with a prosthetic.

What does diabetes do to feet?

So, why should those of us who are challenged in our processing of sugar get problems with our feet?

There’s two main processes at play that lead to foot disease in people with diabetes:

- Atherosclerosis (Blood flow problems)

This is a problem in the general population as well as in people with diabetes, but the way that it affects people with diabetes is slightly different.

In the general population this often affects bigger vessels, higher up in the leg, whereas in people with diabetes it affects smaller ones, below the knee, more commonly.

A combination of glycosylation (glucose sticking to things) and cholesterol build up causes inflammation in blood vessels, making their walls thicker and so making it more difficult for blood to flow through them.

- Neuropathy (Nerve problems)

In the same way that glucose can cause problems when it sticks to the inside of blood vessels, it can also stick to nerve fibres. This causes nerves not to work properly, can can either cause them to lose their protective coating (meaning they don’t transmit signals as well as before) or to die altogether (meaning signals can’t be sent to the brain at all.

This kind of damage is what causes some of the early symptoms of neuropathy, like tingling and numbness.

Ok, but why are these a problem?

This damage to nerves can cause some big problems, the first thing we’ll look at is injuries to feet, the second is damage to the joints of the feet themselves.

- Foot Ulcers

If you can’t feel your feet as well, then it’s much easier to cause them damage. We all bumble around and stub our toes, pick up little cuts, get splinters, gotten into a bath that’s too hot etc all the time.

When you don’t have neuropathy the way you know you’ve done this is feedback from your feet to your brain – normally in the form of pain. Damage to the nerves means that these pain signals are either much more faint, or absent altogether. This means that you can stand on some broken glass, and cut your foot, and not know you’ve done it.

If you’ve broken the skin on the bottom of your feet, and you can’t feel that you’ve done it, then you might not have any idea there’s a problem. That little bit of glass might still be inside, coated in germs from the outside world.

The glass might sit there for a few days before either working its way out, or the skin over the top healing with it still inside. The germs that it has carried inside can start multiplying, and before you know it there’s an infection under the skin in your feet. These infections can affect the skin (cellulitis) or, much more seriously, the bones (osteomyelitis).

With poorer blood flow going to the foot, the white blood cells that the body produces to fight infections might not be able to get to the infection in the numbers they need to, and the bugs can multiply away unchecked.

This infection can lead to a breakdown of the tissues of the foot – and as the tissues break down more of the inside of the foot becomes exposed to the outside world – this is an ulcer.

Ulcers are hard to heal in people with diabetes, because they need good blood flow to help them to get better and putting pressure on them slows down healing too – and people with diabetes often find it harder to heal quickly anyway. These ulcers often need lots of careful attention from a combination of people – most often podiatrists and specialist nurses who look after wounds (Tissue Viability Nurses).

- Charcot Joints

The other way that damage to nerves can do damage to feet is related to the lack of information sent from the feet to the brain. As we walk around, our muscles and joints are constantly telling our brain where they are in relation to all of the other muscles and joints. This is how we are able to move around in a stable and coordinated fashion.

If nerves are damaged, this information no longer reaches the brain, and so it’s harder to coordinate this movement as well as before. This means that with each step taken you might put your weight on your foot in a very slightly awkward way, putting your weight through the joints between all of the bones in your feet (33 joints between 26 bones, per foot!) in a way that’s not quite what’s intended.

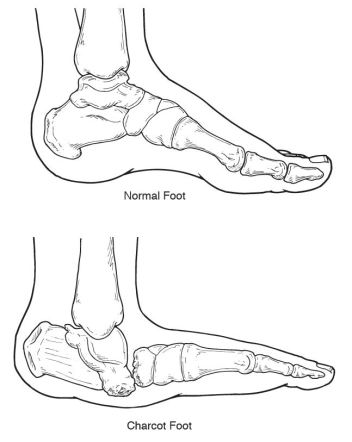

This can cause tiny injuries that you wouldn’t notice called microtrauma. Repeated tiny injuries can cause the joint to change shape as the bones become inflamed and get gradually pushed out of position. The nerves supplying some of the smaller muscles can also be damaged, and this can cause the muscles to put pressure on the joints, causing the foot to change shape. People with a Charcot joint often have one foot that looks ‘shorter’ than the other.

These injuries don’t normally affect the toes – they are normally further back in the foot, most commonly in the joints between the bones that go on to form the toes and the bones that sit directly below the ankle.

Most often, these kinds of joints are diagnosed when a person with diabetes starts to notice a change in the shape of their foot, or notices swelling – although in extreme cases it may not be spotted until there is a break in the skin as the bones cause pressure against the skin from the inside.

The way these problems are treated is usually focused on preventing any worsening of the damage. This is often though careful watching of the foot at frequent appointments with the podiatrist, but also by using special shoes to ‘off-load’ the affected joint, to reduce the chance of more pressure making things worse.

Well, that all sounds awful but what am I supposed to do about it?

So, as with all things diabetes, up front is the usual message we’ve all heard a million times. The better your blood sugar control, the less chance of things like this affecting you. I can feel you all, rolling your eyes. I rolled my eyes as I wrote it.

That said, even those with good blood sugar control might experience some amount of neuropathy eventually. Luckily there are some really easy things we can all do to try to prevent this from progressing to an ulcer or a Charcot joint.

- GET YOUR FEET CHECKED

Having a regular foot check is one of the 15 Healthcare Essentials for people with diabetes. This should happen at least once a year, but if you are starting to have problems with your feet, it should happen more frequently.

If you have to go into hospital for any reason, someone should usually ask you about – and examine – your feet at this opportunity too.

Feet are a bit gross, but doctors and nurses knew what they were signing up for and won’t be put off, so don’t be self-conscious. Whip those socks off.

Doctors and Nurses: we might be shy about getting our feet out. Help us out by suggesting you look at them, because we’re not likely to volunteer them.

- CHECK YOUR OWN FEET

In between having your GP, Practice Nurse, DSN or Consultant check your feet, you should also check your own feet as often as possible – ideally everyday – to check for any redness, swelling, any cuts or scrapes, and any hard skin or cracking.

If you’re not flexible enough to look at the soles of your own feet (we’ve all had days where we’re feeling a bit stiff!) then you could ask someone else to have a look – or you can use a mirror (propping a mirror at an angle by the skirting board next to your bed should give you a great view!).

Every so often it’s worth getting someone else to tickle your feet to check that you can still feel them. There’s a really quick way to test this at home using the Ipswich Touch Test– anyone can do this test!

- TAKE CARE OF YOUR FEET

There’s a few things that are important to do to keep your feet on top form on a day to day basis:

- Keep your toenails nice and neat

- Wear decent shoes – shoes that rub and cause blisters are not your friend!

- Before getting dressed, make sure your feet are nice and dry – especially between the toes

- If you are getting hard skin on your feet, it’s important to moisturise them to keep the skin nice and flexible.

There’s also a few times that it’s important to be a bit more careful of your feet, for example when outside or on the beach. It it’s nice to feel the sand between your toes, but sharp bits of shell can lurk ready to poke holes – and so while walking along the beach a pair of flip flops might be a good idea.

Finally, the most important piece of advice, if you are every worried about your feet – get some advice as soon as you can

Thanks for your post.

LikeLike